Walking with GIANTS: A Living History of Juvenile Justice Systems

In the United States, the development of a juvenile justice system begins on the east coast—in New York and Massachusetts—and moves west to Illinois, and then emerges in California’s first moments as a state.

In the 1850s and 1860s, recent Euro-American immigrants pressured California state officials to establish a system to tame what they perceived as a growing menace to society: youth crime. Social and political leaders studied the existing policies and systems of incarceration across the United States, proposing new and innovative approaches to youth crime. State officials instead chose to adopt outdated, less costly methods, paving the way for the crimnalization and institutionalization of children and youth that continue today in detention, long-term sentencing, and life sentences without parole for youth who commit crimes.

In recent years, California has been leading the way on reform efforts and creating a model for the nation. In particular, California has adopted several bills that have radically reshaped age requirements on various crimes and take a bold stance on recognizing the importance of ensuring that children, whose brain development are not yet complete, are protected from being treated as adults by the criminal justice system. Despite these efforts, there are still 6,500 people who were under the age of 18 at the time of their crime currently serving time in California prisons.

small as a GIANT aims to shed light on this important human rights issue, to support communities in better understanding the plight of children in the justice system, and to move all of us to continue to take action and protect the most vulnerable members of our society: children.

A History of Juvenile Justice across the Nation

1825

The New York House of Refuge is established to address child poverty through detaining and housing poor, vagrant youth who are thought to be on the path to delinquency. The House of Refuge provides youth with education, religious training, and trade apprenticeships. As the number of houses of refuge grow across the country, they eventually form the structure of the juvenile justice system in America.

1899

The first juvenile court was established in Cook County, Illinois.

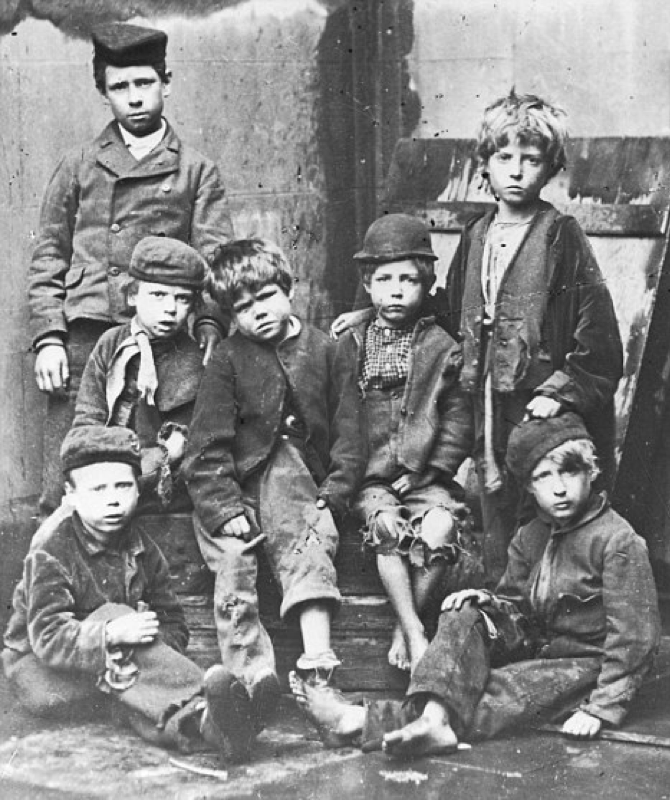

An influx of immigrants to the United States in the 19th century helps pave the way for the development of a separate system of justice for juveniles. Urban youth and the children of immigrants are thought to be more prone to deviant and immoral behavior than other youth. The state, by taking on the functions and responsibilities of a parent, can intervene and interrupt the bad influences of immigrant parents and urban settings.

Two principles from the English court system influence the US juvenile justice system:

• Parens Patriae (parent of the country) was adopted by 15th century English courts to provide the state with the power to substitute their authority for that of birth parents in order to intervene in the lives of children whose deceased parents passed on an estate.

• In Loco Parentis (in place of the parents) was a legal doctrine to allow an individual or an organization to take on the responsibilities of the parent in order to assist needy women and children.

1944

In Prince v. Massachusetts, the Supreme Court rules that no minor boy under 12 or girl under 18 shall sell newspapers, magazines, periodicals, or other articles of merchandise in the streets or other public places. The ruling is followed by many laws that target juveniles for acts of vagrancy and pauperism.

1966

In Kent v. United States, the Supreme Court rules that children considered for transfer to adult court need a judicial hearing to document findings and cause to transfer.

1967

In In re Gault, the Supreme Court rules that juvenile offenders are entitled to the same due process as adult offenders, including the right to timely notification of charges, the right to confront witnesses, the right against self-incrimination, and the right to counsel.

1970

In In re Winship, the Supreme Court increases the burden of proof in juvenile court cases from “preponderance of the evidence” to “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

1971

In McKeiver v. Pennsylvania, the Supreme Court rules that juveniles are not entitled to trial by jury in a juvenile court proceeding.

1985

Beginning in 1985, a series of lawsuits are filed on behalf of immigrant children who have been detained by the former government agency Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). Flores v. Reno challenges the process of detention, treatment, and release of children, as well as the conditions of facilities where children are held. After more than a decade in the court—including an appeal to the Supreme Court—the US government agrees in the 1997 Flores Settlement to set standards for immigration detention centers where children are held, to release children from immigration detention centers without unnecessary delay and, if a suitable placement is not immediately available, to place children in the “least restrictive” setting appropriate to their age and any special needs.

In 2018, as part of a zero-tolerance policy towards undocumented immigrants crossing the border to seek refuge, the Trump administration proposes regulations to terminate safeguards for immigrant children under the Flores Settlement.

1986

Following the death by overdose of University of Maryland basketball star Len Bias, the federal government establishes mandatory minimum sentences for possession of specific amounts of cocaine. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 also sets a 100:1 sentencing disparity for distribution of cocaine—someone would have to distribute 500 grams of powder cocaine to receive the same five year federal sentence for distribution of 5 grams of crack cocaine. Because of its relative low cost, crack cocaine is more accessible to people of color and those living in poor communities, while powder cocaine is more expensive and more often used by affluent white Americans.

Though not particularly directed at juveniles, this law has a devastating impact on poor communities of color across the country. It would not be until 2010 that Congress passes the Fair Sentencing Act—not to eliminate disparity in sentencing, but only to reduce it to 18:1.

1990

As part of the 1990 Convention on the Rights of the Child, the United Nations Agreement to End Juvenile Life Without Parole states that no child should be “subjected to torture or other cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment or punishment.” The human rights treaty also rules that neither capital punishment nor life imprisonment without the possibility of parole should be allowed for anyone under the age of eighteen. The United States is the only country in the world that permits youth to be sentenced to life without the possibility of parole.

1990s

Between 1992 and 1997, in an attempt to combat juvenile crime, new laws make it easier to transfer juvenile offenders to the adult system, provide juvenile courts expanded sentencing options, and remove confidentiality provisions—making juvenile records and proceedings accessible to more individuals and agencies.

1996

The idea of “super-predators”—a generation of young people who are more ruthless, vicious, and less amenable to change —is popularized by the book Body Count, written by John DiIulio, William Bennett, and John Walters. A public discussion about violent youth—particularly Black teenagers—leads to increasing sanctions and the criminalization of youth, accompanied by the implementation of policies and practices that dramatically increase the transfer of youth to the adult system.

2005

In Roper v. Simmons, the Supreme Court outlaws the death penalty for juveniles, deeming it a disproportionate punishment. The court takes into account youth immaturity, diminishing their culpability or responsibility for their actions, and recognizing youth susceptibility to outside pressures and influences.

2010

In Graham v. Florida, the Supreme Court rules that juveniles not convicted of homicide cannot be sentenced to life without the possibility of parole.

In the Fair Sentencing Act, Congress reduces the sentencing disparity for distribution of crack cocaine and powder cocaine from 100:1 to 18:1.

2012

In Miller v. Alabama and Jackson v. Hobbs, the Supreme Court rules that mandatory juvenile sentences of life without the possibility of parole are unconstitutional and violate the Eighth Amendment.

2016

In Montgomery v. Louisiana, the Supreme Court rules that the 2012 Miller decision will be applied retroactively. This ruling does not require states to re-litigate every case where a juvenile received a mandatory life sentence, but requires that those serving juvenile life without parole sentences for homicides would have a parole hearing.

2018

The Trump administration begins a “zero-tolerance” policy at the US border. In April 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announces a policy that directs federal prosecutors to criminally prosecute all adult migrants entering the country illegally. Families are separated and children are held in detention facilities without their parents; “tender age” facilities are used for children under the age of thirteen. Two months later, President Trump signs an executive order to keep together immigrant families detained at the border. Within a week, a California Federal Judge orders US immigration authorities to reunite separated families within thirty days. As of January 2019, more than 10,000 migrant minors are still held in over 100 shelters across the country; at least one for-profit facility is housing nearly 1,600 migrant children.

2019

For the first time in sixteen years, Congress passes a bill reauthorizing the 1974 Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act. The Act addresses racial inequality in the criminal justice system and aims to keep children out of adult jails. Though this is a progressive step, potential new additions to the bill could strengthen these protections further and mandate that states develop programs to address high rates of arrest and detention of youth of color.

History of Juvenile Justice in California

1850

California becomes an official state of the Union.

1860s

By the 1860s, recently arrived Euro-American immigrants to California perceive rates of juvenile crime to be increasing and eventually pressure California representatives to deal with this “growing menace to society.” State leaders begin studying prison policies already in place across the country with the intention of modernizing the system and taking control of their youth population. Several cutting-edge approaches are proposed but officials ultimately adopt outdated methods that lead to increased institutionalization of juveniles. This system grows to become the current model used where racial and ethnic minorities are systematically marginalized and criminalized.

1890

Arthur, an eleven-year old Mexican American from San Francisco, was a resident at the Whittier State School. Although Arthur was intelligent, he was seen as a troublemaker. The reform school housed delinquent and dependent children between the ages of 10 and 18. A few months after being released from the school, Arthur was arrested for burglary. As Arthur was believed to be too old for reform school, he was sent to San Quentin State Prison, established in 1852. Sadly, arrests and detentions became a pattern for Arthur. After his release from San Quentin, Arthur was picked up again and sent to Folsom State Prison. He was eventually released from Folsom, but little else is known of what became of him. (Adapted from States of Delinquency by Miroslava Chavez-Garcia, 2012).

1940–1970

Several moments in history led to a significant increase in the negative impact of all systems of government—including the justice system—on people of color and those struggling with poverty.

Postwar Migration

Due to the rapid growth of industrial employment opportunities during World War II, a nationwide migration of 8–10 million workers occurs; 1.3 million people arrive in California. Many migrants move west from the Southern states; it is estimated that 5 million Black people moved west in the postwar years.

Housing Crisis & Segregation

Between 1940 and 1970, the US population grows by more than 50 percent. Due to government incentives, home ownership soars to unprecedented levels after World War II and the majority of the United States becomes a suburban nation. In the 1960s and 1970s, with the extension of metropolitan freeways, a second phase of suburban growth unfolds.

Racial segregation in major cities continues as a consequence of wartime migration. In Los Angeles, Black people are segregated in the south-central portion of the city and in Little Tokyo—now called Bronzeville—following the 1942 incarceration of the Japanese American community in internment camps. Property owners in adjacent white cities block expansions of their districts by refusing to sell or rent to people of color.

In the Bay Area, Black people are segregated to West Oakland, Richmond, and a few San Francisco neighborhoods. This segregation increases the existing wartime housing shortage, which results in severe crowding in Black neighborhoods.

White Flight

After World War II and the subsequent housing boom, white families move to suburban areas. People of color are stopped from joining the migration to the suburbs due to discrimination and segregation. This dramatically alters the racial demographics of cities across the US and cities become increasingly associated with people of color.

1980s

Gangs

The 1980s bring an increased interest in and crackdown on “gangs.” The federal definition of gangs used by Department of Justice is adopted by individual states, and throughout California —including the Los Angeles Police Department:

“An association of three or more individuals whose members collectively identify themselves by adopting a group identity, which they use to create an atmosphere of fear or intimidation, frequently by employing one or more of the following: a common name, slogan, identifying sign, symbol, tattoo or other physical marking, style or color of clothing, hairstyle hand sign or graffiti. Whose purpose in part is to engage in criminal activity and which uses violence or intimidation to further its criminal objectives. Whose members engage in criminal activity or acts of juvenile delinquency that if committed by an adult would be crimes with the intent to enhance or preserve the association’s power, reputation or economic resources.”

Gang Injunctions

By the mid-1980s, Los Angeles law enforcement begins to use gang injunctions—restraining orders that apply restrictive rules to a group’s behaviors and activities. These orders have requirements that include: evidence that an identifiable gang is engaging in “nuisance activity” within a specific geographic area; that this activity includes violence, drug dealing, illegal weapons, destruction of property, harassment of community members, or retaliation; and that the use of a gang injunction will reduce this activity.

In Los Angeles, gang injunctions are used to blanketly arrest people of color: prosecutors file a civil lawsuit claiming that the gang behavior harms the community. As gangs are not considered formal organizations and typically do not have legal representation, the targeted gang members do not appear at trial. Because the indiviuals are not present in court to represent themselves and argue against the injunction, injunctions are granted by default. Law enforcement then serves assumed gang members with a copy of the injunction days (and sometimes years) later. Although it is possible to challenge an injunction, gang members must first prove they are not gang members without knowing why the city claimed they were gang members in the first place.

Sentencing Enhancements

The 1988 California Street Terrorism Enforcement and Prevention Act (STEP Act) states that anyone who commits a felony on behalf of a gang will receive a mandatory sentence of 2–15 years both in addition to and consecutive to the sentence received for any original felonies.

1980s–1990s

The Crack Epidemic & Tough on Crime

Over the last forty years, beginning in the 1980s, rates of incarceration for people of color have quintupled and drug offenses account for more than half the increase in state prison populations.

Even though drug crime is declining during the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan declares a renewed commitment to the War on Drugs. The war is primarily waged in poor communities of color, particularly Black communities, even though research shows that white youth were (and are) significantly more likely to use and sell drugs than black youth. With racial politics driving this war, Black people are targeted, arrested, and disproportionately fill prisons and jails.

A major driving factor of this racial disparity is the 100:1 sentencing disparity between crack cocaine and powder cocaine; a person would have to possess 100 times as as much powder cocaine versus crack cocaine to trigger the same mandatory sentence. Because of its low cost and greater availability in Black communities, Black people are being arrested for crack cocaine offenses at disproportionate rates. It would not be until 2010 when Congress would pass the Fair Sentencing Act that the ratio would drop from 100:1 to 18:1.

Between 1988 and 1996, President Clinton cracks down harder on drug offenses, delivering a “tough on crime” agenda that devotes billions of dollars to the drug war and passes harsh mandatory minimum sentences for drug crimes.

Though not all these policies were specifically directed at youth, and many were federal level policies, they serve to further devastate entire families and communities, creating more pathways for youth to become involved with the system in California and across the nation. Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow, writes that, “There are more African Americans under correctional control today—in prison or jail, on probation or parole—than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began.”

2003

Farrell v. Harper is filed against the California Youth Authority, citing widespread abuse and neglect of youth in state facilities. When the case settles in 2016, the Department of Juvenile Justice has already taken over the California Youth Authority and implemented a comprehensive system to address education, medical care, sexual assault and harassment, safety, and effective rehabilitation services.

2007

Senate bill 81

Senate Bill 81, also known as the Juvenile Justice Realignment Bill, limits the types of nonviolent offenders who can be committed to state youth correctional institutions and provides funding to county probation systems to improve their capacity to handle higher risk offenders.

2008

The California Little Hoover Commission is established to examine the efficiency of state government operations and consists of a bipartisan board and a subcommittee that supervises public hearings regarding juvenile justice issues. The Commission recommends the closure of the Division of Juvenile Facilities.

2012

Assembly bill 1729

Assembly Bill 1729, also known as the School Suspension and Expulsion Bill, expands and re-defines the list of school-based behaviors, including bullying, that constitute grounds for student suspension or expulsion. AB 1729 also authorizes school districts to document additional responses to this behavior in the student’s official record. School suspensions and expulsions are linked to higher rates of juvenile detention and incarceration and contribute to the school to prison pipeline.

Senate Bill 9, also known as the Juvenile Life Without Parole Sentences Bill, provides for periodic review and resentencing of Juveniles Life Without Parole sentences. Because of this ruling, anyone who was under the age of eighteen at the time of their crime can petition the court to consider a re-sentencing of their case.

2013

senate bill 260

Senate Bill 260, also known as the Youth Offender Parole Hearings Bill, requires the Board of Parole to conduct a “youth offender parole hearing” instead of an adult parole hearing and to consider release of offenders who committed specified crimes and were sentenced to state prison prior to being eighteen years old. The youth offender hearing takes the age and brain maturity of the offender into consideration when deciding on their release.

2014

Proposition 47

Proposition 47 classifies “non-serious, nonviolent crimes” as misdemeanors instead of felonies unless the defendant has prior convictions for murder, rape, certain sex offenses, or certain gun crimes.

2015

senate bill 261

Senate Bill 261, a revision of SB 260, requires the Board of Parole to conduct a “youth offender parole hearing” instead of an adult parole hearing, to consider release of offenders who committed specified crimes and were sentenced to state prison prior to being twenty-three years old.

2016

Senate bill 527

Senate Bill 527, also known as the Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Grant Program, is written under Proposition 47 to establish the Learning Communities for School Success Program. This program controls the allocation of Department of Education funds used to support evidence-based, non-punitive practices that keep vulnerable youth in schools by addressing school climate, student engagement, and healthy accountability.

2018

Senate Bill 10

Senate Bill 1391 repeals a prosecutor’s authority to transfer a minor, who is alleged to have committed certain serious offenses, from juvenile court to adult court if he or she were fourteen or fifteen years old at the time of the offense.

In August 2018, Senate Bill 10 is signed into law. SB10 aims to change California’s pretrial release from a money-based system to a risk-based release or detention: defendants would complete a risk assessment of low, medium, or high risk to determine their likelihood of returning for court appearances. The money bail industry, which would have been put out of business under the new system, collects enough signatures to put SB10 on the November 2020 ballot for a direct voter decision. Many advocates who oppose money bail also stand in firm opposition to risk assessment tools as they are likely to exacerbate already existing racial disparities in the system.

In Los Angeles, the American Civil Liberties Union files a lawsuit against the use of gang injunctions. As individuals rarely get the opportunity to challenge the injunctions in court, these individuals suffer a due process violation of their constitutional rights. As a result of a consent decree, the city is barred from enforcing nearly all of its remaining gang injunctions. These injunctions disproportionately target Black and Latino communities because of their broad nature, including otherwise legal behavior like being outside after dark or wearing certain clothes or colors and their ability to sweep up anyone who knows or is related to a gang member.

Ab 1308

AB 1308 expands the opportunity for a “youth offender parole hearing” – instead of an adult hearing – for people who were 25 or younger at the time of their crime.

2019

SB 394 provides people who committed crimes at 16 or 17 and sentence to life without parole a chance to earn parole, with the first parole hearing possible after 24 years of incarceration.

-Timeline Last Updated December 2019-

References

Alexander, M. (2010). The War on Drugs and the New Jim Crow. Race, Poverty, and the Environment, 17(1), 75–77.

American Bar Association Division for Public Education. (n.d.). The History of Juvenile Justice: Part 1. Dialogue on Youth and Justice, 4–8.

American Civil Liberties Union (2010). “Fair Sentencing Act.”

Ballotpedia. (2014). California Proposition 47, Reduced Penalties for Some Crimes Initiative (2014).

Burnett, J. (2019, January 17). “Federal Immigration Agents Separated More Migrant Children Than Previously Thought.” NPR.

California Department of Transportation. (2011). Tract Housing in California, 1945–1973: A Context for National Register Evaluation.

Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice. (2018). Juvenile Justice History. CJCJ.

Chavez-Garcia, M. (2012). States of Delinquency: Race and Science in the Making of California’s Juvenile Justice System. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse, University of Michigan Law School (n.d.). Case Profile:

Farrell v. Harper.

Commonweal: The Juvenile Justice Program. (2012). Juvenile Justice and Youth Crime & Violence Prevention Bills: Summary of Bills Signed or Vetoed by the Governor.

Commonweal: The Juvenile Justice Program. (2016). Juvenile Justice and Related Youth Program Bills in the 2016 Session of the California Legislature. COMJJ.

Custer, L. B. (1978). The Origins of the Doctrine of Parens Patriae. Emory Law Journal, 27, 195.

Feld, B. (2004). Juvenile Transfer. Criminology and Public Policy, 3(4), 599-604.

Fuller, T. (2018). California is the First State to Scrap Cash Bail. The New York Times.

Hegarty, A. (2018). Timeline: Immigrant Families Separated at the Border. USA Today.

Human Rights Watch (2017). Youth Offender Parole: A Guide for People in Prison and Their Families and Friends. Human Rights Watch.

Jordan, M. (2019). Trump Administration to Nearly Double Size of Detention Center for Migrant Teenagers. The New York Times.

Lawrence, R. & Hemmens, C. (2008). Juvenile Justice: A text/reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

McGough, M. (2019). The Fate of California’s Cash Bail Industry Will Now be Decided on the

2020 Ballot. The Sacramento Bee.

National Conference of State Legislatures (2017). Miller v. Alabama and Juvenile Life Without Parole Laws.

Nelson, L. & Lind, D. (2015). The School to Prison Pipeline, Explained. Justice Policy Institute Retrieved from http://www.justicepolicy.org/news/8775

Ochoa, M. (2018). LAPD Gang Injunctions Gave Cops a License to Harass and Control Black

and Latino Residents. ACLU. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/blog/criminal-law-reform/reforming-police-practices/lapd-gang-injunctions-gave-cops-license-harass.

Prison Law Office. (2019). Major Cases. Prison Law.

Prison Public Memory Project. (2014). House of Refuge for Women, 1887–1904. Prison Public Memory.

Torbati, Y.T & Cooke, K. (2019, February 14). “First Stop for Migrant Kids: For Profit Detention Center.” Reuters.

Rovner, J. (2017). Juvenile Life Without Parole: An Overview. Washington, DC: The Sentencing Project.

Senate Committee on Public Safety. (2018). SB 1391 Juveniles: Fitness for Juvenile Court.

Shouse California Law Group. California’s Gang Sentencing Enhancement Law Penal Code 186.22 PC Explained by Criminal Defense Lawyers. Shouselaw.

Snyder, H. N., & Sickmund, M. (2006). Juvenile Offenders and Victims: 2006 National Report.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, & Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Stracqualursi, V., Valencia, N. & Kopan T. (2018). Toddlers, Babies Held in ‘Tender Age’

Facilities After Separated from Families. CNN.

Superior Court of the State of California, County of Alameda. (2016). Farrell v. Kernan Stipulation and Order Dismissing Consent Decree with Prejudice. PrisonLaw.

US Supreme Court. (1944). Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158. SupremeJustia.

US Supreme Court. (2015). Senate Bill No. 261. California Legislative Information.

US Supreme Court. (2018). Senate Bill No. 10. California Legislative Information.

Vagins, D. J. & McCurdy, J. (2006, October 26). “Crack in the System: Twenty Years of Unjust Federal Cocaine Law.” ACLU.